CANDICE LIN

PIGS AND POISON

5 February to 8 May 2022

Spike Island presents Pigs and Poison, a major new commission by LA-based artist Candice Lin that expands her ongoing research into marginalised histories, colonial legacies and the materials that link them. Combining materials as diverse as opium poppy, bone black pigment and lard, the exhibition weaves together wide-ranging stories of migration, biological warfare, and British and American colonial relationships with China to explore how Asian people have often been defined in relationship to animality, contagion, and the inhuman. Lin traces how these definitions have subsequently influenced constructions of whiteness and citizenship in the United States.

The title of Lin’s exhibition refers to the trade in Chinese indentured labourers (disparagingly known as ‘pigs’) and opium (poison) during the nineteenth century. This period brought about the two Opium Wars that marked the start of an era of unequal treaties between China and foreign imperialist powers, including strict immigration laws that eventually led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States: the first law to disallow immigration on the basis of race, regardless of nationality.

The centrepiece of Pigs and Poison is a monumental trebuchet that launches cannonballs made of lard and bone black pigment at the gallery walls. This work references an early example of biological warfare: the 1346 siege of Caffa (now Feodosia, Crimea), when the attacking Mongol army catapulted the plague-infected corpses of people and horses inside the city walls. When the siege broke, the people who fled the city with their lives supposedly first brought the plague to Europe.

Purring, flesh-like sculptures reference the plague-ridden Mongol corpses and accompany a series of small-scale lard paintings highlighting plague outbreaks in San Francisco and Honolulu at the turn of the twentieth century, for which Chinese citizens were held responsible and subsequently victimised.

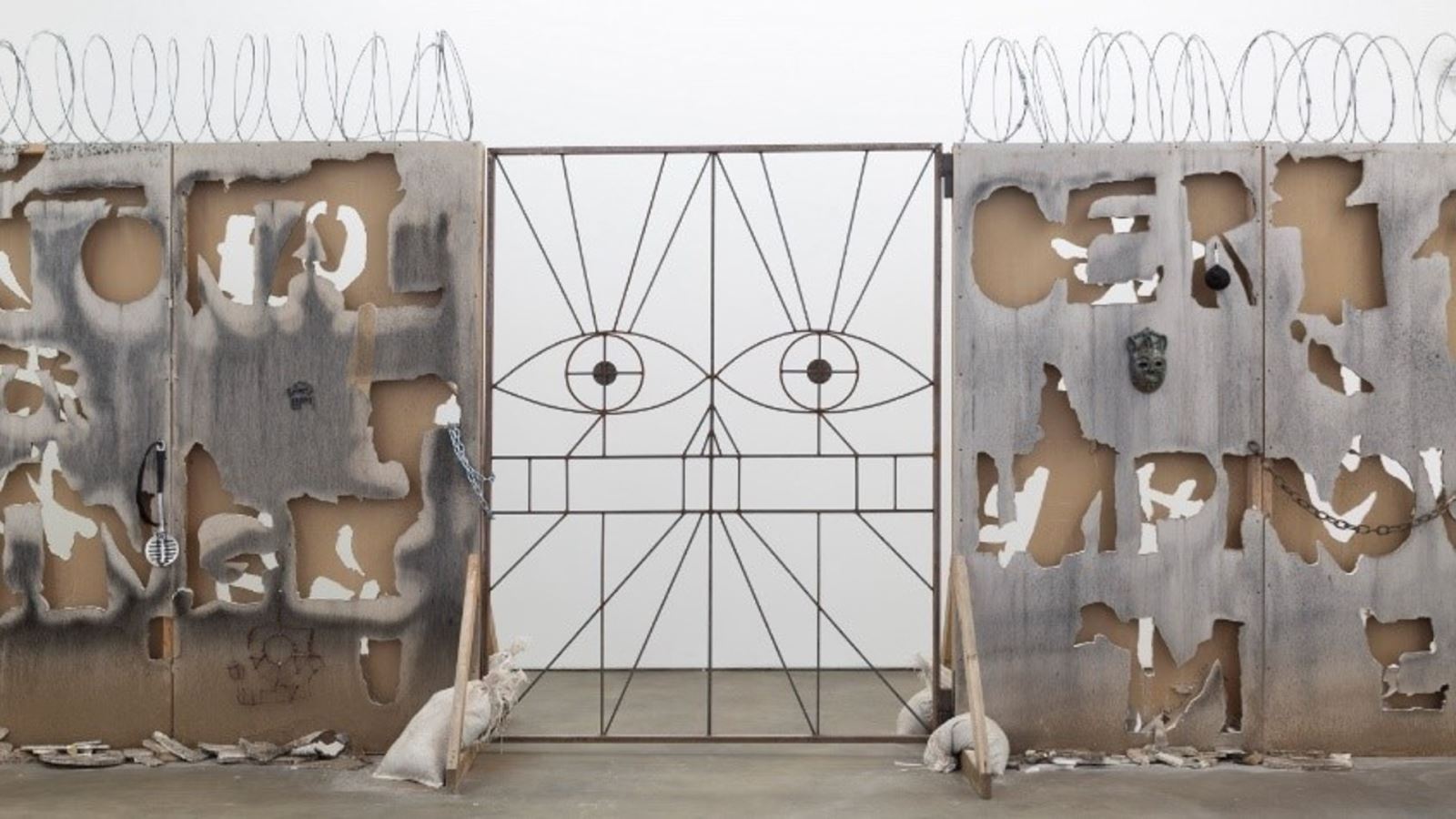

The viscous cannonballs soar over a roughshod barricade topped with barbed wire that divides the main gallery space, creating an encrusted, blue-black painting on the wall. Carved into the border is the phrase “meaningless squiggles” in both English and Mandarin, translated via Google Translate and drawn in Lin’s dad’s calligraphy. The phrase is taken from American Philosopher John Searle’s 1980 essay ‘Minds, Brains and Programs’, in which he first developed to so-called ‘Chinese room’ theory to distinguish, via his own inability to understand Mandarin, between AI and human consciousness. This work references the long history of Asiatic otherness being associated with a robotic lack of humanity or emotion, as well as exploring how cultural signifiers often fade or shift over time within diasporic communities.

As the world grapples with closing borders, lockdowns, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and a rise in racial tensions, Lin’s exhibition has an uncanny relevance in the UK today. In our short-sighted fight to control and contain, we lose track of how the connections between race, labour and illness have shaped continents, hierarchies and histories for many centuries.

Related

Comments

Nobody has commented on this post yet, why not send us your thoughts and be the first?